AI and the Commons

AI breaks the open-source business model—not the machine

Recently I stumbled upon a tweet by an open-source maintainer, ranting about AI and how it affects his ability to monetize his OSS project (emphasis mine):

All my new code will be closed-source from now on. I’ve contributed millions of lines of carefully written OSS code over the past decade, spent thousands of hours helping other people. If you want to use my libraries (1M+ downloads/month) in the future, you have to pay.

I made good money funneling people through my OSS and being recognized as expert in several fields. This was entirely based on HUMANS knowing and seeing me by USING and INTERACTING with my code. No humans will ever read my docs again when coding agents do it in seconds. Nobody will even know it’s me who built it.

Look at Tailwind: 75 million downloads/month, more popular than ever, revenue down 80%, docs traffic down 40%, 75% of engineering team laid off. Someone submitted a PR to add LLM-optimized docs and Wathan had to decline - optimizing for agents accelerates his business’s death. He’s being asked to build the infrastructure for his own obsolescence.

Two of the most common OSS business models:

Open Core: Give away the library, sell premium once you reach critical mass (Tailwind UI, Prisma Accelerate, Supabase Cloud...)

Expertise Moat: Be THE expert in your library - consulting gigs, speaking, higher salary

Tailwind just proved the first one is dying. Agents bypass the documentation funnel. They don’t see your premium tier. Every project relying on docs-to-premium conversion will face the same pressure: Prisma, Drizzle, MikroORM, Strapi, and many more.

The core insight: OSS monetization was always about attention. Human eyeballs on your docs, brand, expertise. That attention has literally moved into attention layers. Your docs trained the models that now make visiting you unnecessary. Human attention paid. Artificial attention doesn’t.

Some OSS will keep going - wealthy devs doing it for fun or education. That’s not a system, that’s charity. Most popular OSS runs on economic incentives. Destroy them, they stop playing. Why go closed-source? When the monetization funnel is broken, you move payment to the only point that still exists: access. OSS gave away access hoping to monetize attention downstream. Agents broke downstream. Closed-source gates access directly. The final irony: OSS trained the models now killing it. We built our own replacement.

My prediction: a new marketplace emerges, built for agents. Want your agent to use Tailwind? Prisma? Pay per access. Libraries become APIs with meters. The old model: free code -> human attention -> monetization. The new model: pay at the gate or your agent doesn’t get in.

I don’t agree with his implication that OSS is now left to “wealthy devs doing it for fun or education.” I do agree, though, that eventually there will have to be some kind of pay per access feature to libraries/content for this to be economically sustainable (see Agentic Web). Despite that, I think open-source won’t die out, even without money in the picture, because:

Programmers will still want to code to contribute to open-source software (with or without the help of AI)

We still benefit immensely from the compounding value of using and looking at the same code. This is because of something called Inverse Tragedy of the Commons. Open-source won’t die out; at least not the ones that the commons care about.

How the Open-Source Machine Works

To understand why open-source won’t die out, and will still be sustainable despite AI, let’s understand how open-source software survive and self-perpetuates across many industries.

I find Eric S. Raymond’s (aka ESR) essays very helpful in explaining why free and open-source works in great detail—which I think can be summarized as a virtuous cycle.

First, for individual programmers, there’s that itch. A programmer will work on the things that they care about the most; if they’re doing it for free, they’re doing it for themselves. Such was how Linux was conceived, and many others that preceded it or followed it. This is especially true when there’s no other (free) software that exists—or (free) software that exists but is deemed not good enough—that solves the programmer’s problem. To quote ESR:

Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer’s personal itch.

Now that a programmer has scratched the itch, either by forking an existing (dead) software, making incremental contributions, or by creating a new one from scratch (pun not intended), what keeps them going? Here lies the question of incentives. If they plan to sell the support or maintenance service (e.g., as with enterprise Red Hat Linux), then the incentive is obvious: money. But what about the software that exists without a business model? If we eliminate money from the equation, what’s the driving force for programmers to maintain and write code, besides the joy of it?

To answer this question, ESR first described two different ways humans commonly organize themselves to allocate scarce resources: command hierarchy and market economy. As the name suggests, command hierarchy follows a top-down approach of central planning that allocates resources for everyone in the organization. Perhaps the most popular example of command hierarchy in history is also a textbook example of why it doesn’t scale well and is bound to crumble: the communism in 20th century Soviet Union failed to deliver its promise—instead of a rich Utopia for the masses, it delivered chronic shortages, breadlines, and eventual economic collapse. The clear winning model for allocating scarce resources is that there should be little to no planning at all; instead, in a market economy, individual transactions are driven by supply and demand. This scales better, as prices become the signal for resource allocation, operated over the exchange of money for goods and services.

Yet neither of these economic models explains the behavior of programmers in the open-source ecosystem: While command hierarchy and market economy are economic models that can explain the allocation of scarce resources, it doesn’t fit well in a world of abundance! Unlike the resources managed in a command hierarchy model or market economy model, software is a resource that can be duplicated with virtually zero cost, at a very large scale and speed, given the abundance of compute, storage, and network bandwidths (thanks to the 90s dot-com bubbles). Abundance, ESR writes, makes “command relationships difficult to sustain and exchange relationships an almost pointless game.”

There’s a third model, however, that can help explain the allocation of resources in the open-source ecosystem characterized by abundance: the gift economy. In contrast to a market economy, where goods and services are exchanged for money, a gift economy operates differently. ESR explained the gift economy through an anthropological lens, using Lockean theory of property ownership as an analogy to explain the motivation behind the ownership and “homesteading” of open-source projects. Here’s how he explained it:

On a frontier, where land exists that has never had an owner, one can acquire ownership by homesteading, mixing one’s labor with the unowned land, fencing it, and defending one’s title. ... A piece of land that has become derelict in this way may be claimed by adverse possession—one moves in, improves it, and defends title as if homesteading. This theory, like hacker customs, evolved organically in a context where central authority was weak or nonexistent.

If we think of the open-source ecosystem as a frontier—ungoverned, with no central authority assigning ownership—it follows that hackers observe the same customs that Lockean theory describes: claim it through labor, maintain it, defend your title. Let a project go unmaintained, and someone else will fork it:

The Lockean logic of custom suggests strongly that open-source hackers observe the customs they do in order to defend some kind of expected return from their effort. The return must be more significant than the effort of homesteading projects, the cost of maintaining version histories that document “chain of title”, and the time cost of making public notifications and waiting before taking adverse possession of an orphaned project.

In other words, open-source software maintainers expect something in return, or a net benefit, for their efforts, even if it isn’t directly about money.

When the exchange of goods and services becomes pointless (everyone has access to all goods and services in the world), monetary exchange currency becomes worthless. ESR argues that the principal currency in a rich society blessed with abundance is reputation:

... prestige is a good way (and in a pure gift economy, the only way) to attract attention and cooperation from others. If one is well known for generosity, intelligence, fair dealing, leadership ability, or other good qualities, it becomes much easier to persuade other people that they will gain by association with you.

Obviously, if your gift is crap, the reciprocal is a crappy reputation. So there has to be some value associated with the open-source software that’s being maintained or built that gives the programmers their expected returns. The higher the value of the software, the better your prestige or status; the better you can make it when you enter the market economy or command hierarchy.

This is another property of open-source software that makes it different from traditional resources: Not only is it abundant (i.e., not scarce), but it also increases in value the more you use or consume it. The other thing I know that has this property is knowledge, which is befitting, since source code can be thought of as an encoding of someone’s or an organization’s knowledge.

ESR called this phenomena Inverse Tragedy of the Commons, after the popular concept called Tragedy of the Commons:

Over every attempt to explain cooperative behavior there looms the shadow of Garrett Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons”. Hardin famously asks us to imagine a green held in common by a village of peasants, who graze their cattle there. But grazing degrades the commons, tearing up grass and leaving muddy patches, which re-grow their cover only slowly. If there is no agreed-upon (and enforced!) policy to allocate grazing rights that prevents overgrazing, all parties’ incentives push them to run as many cattle as quickly as possible, trying to extract maximum value before the commons degrades into a sea of mud.

...

[W]idespread use of open-source software tends to increase its value, as users fold in their own fixes and features (code patches). In this inverse commons, the grass grows taller when it’s grazed upon.

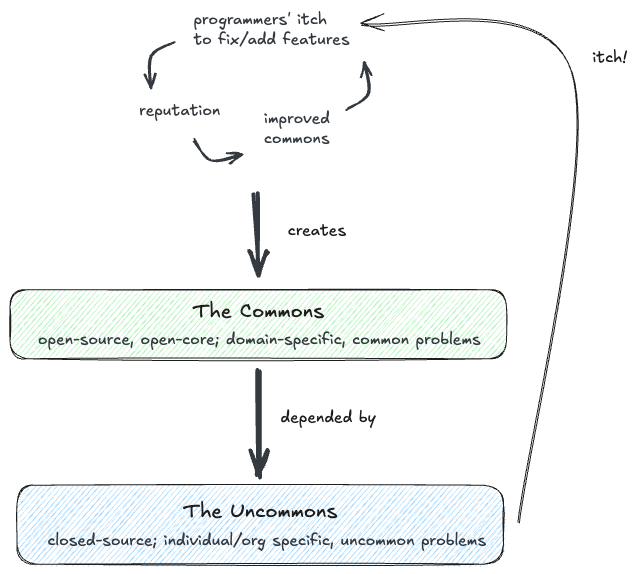

The Inverse Tragedy of the Commons is what completes the open-source virtuous cycle loop. Somewhere down the line there’ll be some disgruntled programmer who uses the commons, creates a patch or adds new features because he has an itch. While doing that, he’s also doing it for himself, to earn reputation, and for self-satisfaction. And the open-source software (the commons) only grows taller.

AI in the Open-Source Machine

If intelligence is one of the ingredients that fuels the open-source machinery and produces free software, then the programmers are vehicles of the intelligence that transforms ideas to runnable software. Yet while intelligence is scarce, intelligent programmers that are willing to write free software are even scarcer!

And then AI comes along, which sort of commoditize intelligence, and suddenly the scarce intelligence becomes abundant. I’ve tried Claude’s Opus 4.5, and so have many others including many veterans in the industry, and there’s no denying that AI will effectively be a huge part of the intelligence that creates software.

What this means to our open-source machinery cycle described above is the following: The cost of scratching an itch is cheaper, either because it takes less time to substantiate code, or because of lower skill ceiling. Whether this is a good thing or a bad thing for the overall quality of open-source source codes, the barrier to entry to scratch an itch is lower. Using the Lockean theory analogy above, one might think that the cost of reaping the benefits of homesteading an open-source project is now cheaper, and thus the return is higher (i.e., it is easier to gain reputation). Unfortunately, that’s not what happens.

A consequence of the lower barrier to entry, however, is that it devalues reputation. Or put in terms of currency, the value of reputation is being inflated. But not all reputation inflates equally: What AI commoditize is the execution—substantiation of code or working the CLI at breakneck speed. What remains scarce is the judgement: identifying which itch is worth scratching, making sound architectural decisions, and stewarding open-source projects over time (i.e., collaborating with some randoms on the Internet, establishing a hacking subculture, etc.)

This is like the barrel vs. the ammunition analogy. From my post Of Kind Chess and Wicked Programming:

This doesn’t mean I completely disregard the notion of AI replacing human programmers in the future. The key difference between the AI we’re using right now and the one that Jensen Huang portends is in their capacity (or lack thereof) to be a manager instead of the individual contributor; to be an architect instead of the builder; or, to borrow Ben Thompson’s analogy, to be an Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI)—the rifle barrel—instead of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—the ammunitions:

What o3 and inference-time scaling point to is something different: AI’s that can actually be given tasks and trusted to complete them. This, by extension, looks a lot more like an independent worker than an assistant — ammunition, rather than a rifle sight. That may seem an odd analogy, but it comes from a talk Keith Rabois gave at Stanford…My definition of AGI is that it can be ammunition, i.e. it can be given a task and trusted to complete it at a good-enough rate (my definition of Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI) is the ability to come up with the tasks in the first place).

In this perspective the future of programming is certainly bright: We may not be too far from a future where we can “hire” cheap individual contributors—the ammunitions—to help generate 100% of the code. But ammunitions are only useful when we—the rifle barrel—point them to the desired targets. It gets trickier in a wicked world, where the targets would often dance unpredictability. Often times, it is even unclear which targets we should point to. In other words, creativity is about knowing what and where to aim; simply being the projectile isn’t!

Back to Marc, the disgruntled open-source maintainer from the tweet above: Marc’s moat—and the foundation of his business model—was knowledge, or specifically, the kind of execution-layer expertise that AI now replicates at scale. His deep contextual knowledge about his own codebase was valuable when humans couldn’t easily acquire it. But now, with AI commoditizing intelligence that can not only easily acquire that knowledge, but also execute on it, his OSS income funnel threatens to collapse.

This is a classic example of how new technology decimates information asymmetry. To quote Freakonomics:

It is common for one party to a transaction to have better information than another party. In the parlance of economists, such a case is known as an information asymmetry. We accept as a verity of capitalism that someone (usually an expert) knows more than someone else (usually a consumer). But information asymmetries everywhere have in fact been gravely wounded by the Internet.

Then it was the Internet; now, AI collapses that information asymmetry even more by not only giving away the information, but also acting on it.

Of course, this is only saying that he’s losing his moat to monetize on his open-source project, but this does not mean that his open-source project is in any way less valuable. In fact, to the community as a whole, his open-source project may get more valuable, thanks to AI agents making it easier (and cheaper) to capture value.

AI doesn’t break the commons, but it does break the existing OSS monetization model. Yet programmers will still want to contribute to open-source projects: The broken monetization model is just one way of converting the currency of reputation to fiat currency in the market economy. AI may break that specific monetization model, but the mechanism of converting reputation to monetary currency hasn’t broken yet.

Pushing the Money Downstream

While AI doesn’t kill OSS, it doesn’t make it any easier for people to make money off it either. If not in the contribution to—or in the possession of knowledge moat of—OSS projects, where can monetary rewards be captured?

I believe OSS will still be alive due to the virtuous cycle I described earlier: Programmers will still get the itch, they will still benefit from the reputation reaped from their OSS contribution in the gift economy, and this in turn will make the open-source ecosystem much better. But while there’s no money to be made in this cycle, there’s money to be captured downstream from the products of this cycle, as illustrated below:

The key difference between the commons and the uncommons lies in the nature of the problems they solve. The commons layer addresses problems shared across a domain—problems whose boundaries often map to industry lines (oil and gas, finance, pharmacy, and so on). Contributors and users benefit from network effects: the more people use and improve the same codebase, the more valuable it becomes for everyone. This isn’t charity either. Every contribution reflects a cost-benefit calculation, whether explicit or intuitive: is it cheaper to privately fork and bear the full maintenance burden, or to contribute upstream and let the community carry the weight?

The uncommons, by contrast, solves problems specific to individuals or organizations—the differentiated logic, the proprietary integrations, the things you don’t want your competitors to have. But because the uncommons depends on the commons, programmers working in the uncommons layer inevitably encounter friction in the foundations they build on. When they do, they face a choice: fork and maintain privately, or fix it upstream. For non-differentiating fixes, contributing back is almost always cheaper. The uncommons doesn’t just extract from the commons—it feeds the commons whenever doing so costs less than going it alone.

It is also interesting to note the dynamic between agentic AI and the commons and the uncommons. Due to AI slops, thanks to unguided code generation, the maintainers of the commons may react negatively to AI generated contributions. More slops means it can take more time, energy, and resources for the maintainers to do code review, which may lead to stricter governance on how code contributions are made, slowing down progress. Downstream in the uncommons, it’s a different story: AI helps individuals or organizations with specific problems in the uncommons, problems that otherwise wouldn’t have been addressed in the commons, and thus are more welcomed. In fact, using AI to aid software development is often encouraged in the name of productivity, as we’ve seen in many enterprises in the past few years. This is because the closed-source projects in the uncommons enjoy the luxury that open-source projects in the commons don’t have: a handful of familiar contributors.

This isn’t really a happy answer for OSS maintainers like Marc, who depends on the moat of deep source knowledge and expertise to fund his projects. With AI easily collapsing that moat, his choice to close-source his future projects behind a paywall is entirely rational, and perhaps necessary for surviving this paradigm shift. Perhaps the only consolation is that his prestige and personal brand—the judgement, taste, and stewardship that AI cannot replicate—remains valuable. The monetization path might have changed, but the currency of reputation hasn’t disappeared.